As part of a semester-long mentorship program through my high school, High Technology High School, I was able to work once a week at the Princeton Plasma Physics lab under Bob Kaita.

Neutrons are released as a byproduct of fusion reactions, like those performed at the NSTX at PPPL. Many of these neutrons escape the magnetically confined plasma and impart a sizeable neutron flux on the plasma-facing components of the tokamak. These components must withstand the neutron flux without becoming too radioactive, which would produce dangerous nuclear waste and require a total shutdown to for replacement. Some common choices are graphite and molybdenum, which are both cheap and strongly resist neutron capture.

A different solution to this problem is the use of liquid metal walls. By placing a constant flow of liquid metal around the central chamber, neutrons are captured and harmlessly flow out. Candidates for this liquid include lithium, a tin-lithium alloy, and gallium. One point of concern, however, is the possible failure of the outer walls in direct contact with the liquid metal due to liquid metal embrittlement, a phenomenon where liquid metal in contact with solid metal diffuses into the bulk and causes corrosion and brittleness.

I operated a device designed to test the effect of liquid metal embrittlement on 316 steel and 1018 steel. 316 steel is a ductile stainless steel, while 1018 steel is a mild carbon steel that is harder and more brittle. These samples were placed under stress and high heat while being soaked in liquid gallium for up to two weeks, in order to simulate the effects of embrittlement. We determined the degree of degredation of these samples with Charpy impact testing, a very fun test that involves hitting things with a big swinging hammer and seeing how much energy it takes to break them.

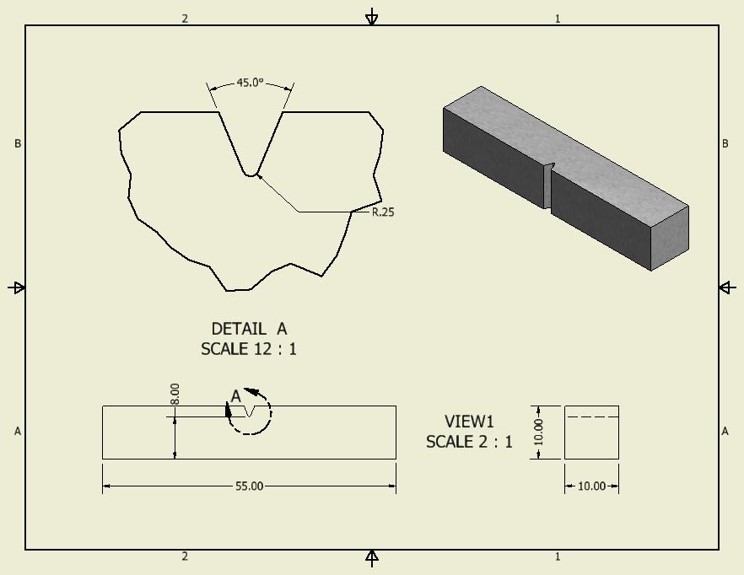

This project was a great example of how easily experiments can go wrong. The 316 steel absorbed all 300 foot-pounds of energy the Charpy could impart, so tests on it were mainly inconclusive. The 300°C testing temperature ended up tempering the 1018 steel, turning it a very cool-looking purple but rendering any embrittlement tests useless. Additionally, to protect the outer frame of the testing device from the gallium, a TZM (titanium-zirconium-molybdenum) cylinder was used to line the central chamber. TZM is a very inert alloy, but repeated stresses both from tension and heat caused it to break twice, meaning that new cylinders had to be machined and inserted before more data could be taken.