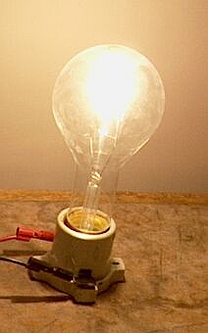

A clear 300-watt bulb with a straight (coiled coil) vertical filament is connected to a variable transformer. As you raise the voltage from zero, thus increasing the current through the filament and raising its temperature, at some point the filament begins to glow dull red. As you continue to raise the voltage to 120 VAC, the filament glows more and more brightly, and the color changes from dull red to bright red, then orange, yellow and then almost white. The relationship between an object’s temperature and the spectrum of the radiation it emits enables astronomers to determine the temperatures of celestial objects.

Anyone who has operated a toaster or used an electric stove has probably noticed that as the heating elements become hot, they begin to glow a dull red, and as they continue to heat up, they glow more brightly and their color becomes light orange. Similarly, as a piece of iron is heated longer and longer in a fire, it begins to glow more and more brightly, and its color goes from a dull red, to orange, then yellow and then white. The incandescent lamp used in this demonstration, operated at different voltages, illustrates this phenomenon.

All solid objects (and bodies of liquid or dense gas) emit a continuous spectrum of radiation because of their temperature. This type of radiation is called thermal radiation. Objects also can absorb thermal radiation from their surroundings. Though the material that makes up an object may have some small effect, the characteristics of the radiation emitted by the object depend mostly on its temperature. People have found by experiment that an object whose surface absorbs all thermal radiation incident upon it, emits a thermal spectrum whose characteristics depend only on its temperature, and that all such objects emit the same spectrum when they are at the same temperature. Since such objects do not reflect any light, they appear black. (One can make such an object by coating any object with a thin layer of flat black pigment.) For this reason, they are called blackbodies, and their emissions are called blackbody radiation. One particular type of radiator that is useful for studying blackbody radiation is a hollow body that has a small hole in its wall, which communicates between the cavity within it, and the outside. Essentially all of the radiation incident on the hole from outside enters the cavity, and essentially none is reflected back through the hole. At a particular temperature, the walls of the cavity emit thermal radiation, some of which exits the hole. The hole thus absorbs and emits as a blackbody would. The radiation from this hole is called cavity radiation, and its properties are identical to those of blackbody radiation.

The function that describes the spectral distribution of blackbody radiation as a function of temperature is called the spectral radiancy, which we can denote RT(ν). It is defined so that RT(ν) dν equals the energy emitted per unit time in radiation having frequencies over the interval ν to ν + dν, per unit area of the radiating surface at temperature T. The integral of this function over the entire range of frequency of the radiation, 0∞∫RT(ν) dν, is the total energy emitted per unit time per unit area, which is called the radiancy, denoted RT. Blackbody radiation has two interesting and important properties, which are indicated by the behavior described above.

The total power per unit area emitted by a heated object, RT, increases steeply with increasing temperature, and its behavior is described by Stefan’s law, which is

RT = σT4,

where σ, the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, equals 5.6704 × 10-8 W/(m2-K4). The change in radiated power with temperature is quite large. For example, doubling the temperature results in a 16-fold increase in the radiancy.

The spectral radiancy, RT(ν), is a smooth curve that rises from zero at ν = 0 to a maximum, then falls back to zero at some large value of ν. (This curve is not symmetrical; vide infra.) The frequency at which the maximum occurs is linearly proportional to the temperature. This is Wien’s displacement law, which stated in terms of frequency is νmax ∝ T. Since λ = c/ν, we can rewrite this as

λmaxT = b,

where b, Wien’s constant, equals 2.898 × 10-3 m-K.

Stefan stated his law in 1879, and Wien formulated his displacement law in 1893. At the time, people were struggling to develop a theoretical model that would accurately describe this behavior, and these laws were determined empirically. Shortly after he stated his displacement law, Wien developed the formula below, to give the emission intensity as a function of wavelength.

Rλ = (C1/λ5)(1/eC2/λT)

Here C1 and C2 are constants that are determined empirically. This formula gave a reasonably good fit to experimental data, but it did not fit to within experimental error, especially at longer wavelengths. Max Planck suggested a modification to Wien’s formula, with which it fit the data precisely, but was still an empirically determined equation. (Planck changed it to Rλ = (C1/λ5)(1/[eC2/λT - 1]).)

Around 1900, among those working on this problem were Lord Rayleigh and Sir James Jeans. They considered the radiation inside a cavity as a collection of standing waves in three dimensions, in equilibrium with the walls of the cavity and with each other. They derived an expression for the number of standing standing waves in the cavity as a function of wavelength, and by applying the law of equipartition of energy under the assumption that the energy in all of the various standing waves (modes) would follow a Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution, they derived an expression for the spectral radiancy of the cavity as a function of temperature and the frequency of the emitted radiation. (As noted above, fixing the temperature yields a plot of radiancy versus frequency for a blackbody at a particular temperature.) This formula was:

RT(ν) = [(8πν2kT)/c3]dν,

where k is Boltzmann’s constant, which equals 1.381 × 10-23 J/K. Unfortunately, while this theory worked well for low frequencies, with increasing frequency the curve it produced began to deviate dramatically from that of the experimental data, and rose sharply toward infinity. This failure of the theory to fit experiment for high frequencies was called the ultraviolet catastrophe.

In formulating their theory, Rayleigh and Jeans assumed that the standing waves in the cavity could have any amount of energy, and that the walls could absorb or emit any amount of energy. According to the law of equipartition of energy, the average energy per mode is kT, and each mode has equal probability of being produced. That the theory agrees reasonably well with experiment at low frequencies indicates that for low frequencies, the average energy per mode equals kT, but at higher frequencies it does not. Experiment indicates that as the frequency approaches inifinity, the average energy per mode goes to zero. Planck suspected that the problem lay in the application of the law of equipartition of energy. If each mode has equal probability of being produced, and the number of modes increases as the square of the frequency, this leads to the failure described above. Planck realized that the average energy must be a function of frequency that approaches kT as frequency goes to zero, and approaches zero as frequency goes to infinity.

In considering the atoms that make up the walls of a cavity as tiny oscillators that emitted radiation into the cavity and absorbed radiation from it, Planck introduced two radical ideas. First, an oscillator cannot have just any energy, but only energies that are proportional to integral multiples of its natural frequency of oscillation, or

E = nhν,

where n is an integer, ν is the oscillator frequency, and h is a constant, now known as Planck’s Constant and equal to 6.626 × 10-34 J·s. Second, an oscillator cannot emit or absorb just any amount of energy, but must emit or absorb energy in specific amounts, called quanta, that are integral multiples of hν. That is,

ΔE = Δnhν.

The energy is said to be quantized. When Planck evaluated the sum over all energies of a Boltzmann distribution with the constraint that the energy was quantized, he obtained the following expression for the average energy per mode:

Eave = (hν)/(ehν/kT - 1)

We can see that as the frequency approaches zero, Eave approaches kT, and as the frequency goes to infinity, Eave approaches zero. (As ν → 0, ehν/kT → (1 + hν/kT), and as ν → ∞, ehν/kT → ∞.) Combining this with the number of allowed cavity modes, Planck obtained the following expression for the spectral radiancy:

RT(ν) = [(8πν2)/c3][(hν)/(ehν/kT - 1)]dν

This is called Planck’s blackbody spectrum, and it agrees completely with experimental data. We should note that as h approaches zero, which would correspond to the energy not having discrete values, the average energy goes to kT, the classical energy, and Planck’s equation reduces to the Rayleigh-Jeans equation. Planck’s introduction of the concept of the quantization of energy led to the solution of one of the major physics puzzles of the time, and the publication of his radiation law in December of 1900 marks the birth of the field of quantum mechanics.

It is usually more convenient to use wavelength instead of frequency. If we substitute c/λ for ν in the equation above, we obtain

RT(λ) = [(8πhc)/λ5][1/(ehc/λkT - 1)](dλ)

One can derive both Stefan’s law and Wien’s displacement law from this equation. Integration over all λ gives Stefan’s law as RT = [(2π5k4)/(15c2h3)]T4, where the quantity in brackets is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant, σ, which as noted above has the experimentally determined value 5.6704 × 10-8 W/(m2-K4). To obtain Wien’s law, we differentiate and set dR(λ)/dλ = 0. This gives λmax = 0.2014 hc/k, where (0.2014 hc/k) is Wien’s constant, b, which as noted above has the experimentally determined value 2.898 × 10-3 m-K. With the speed of light and these measured values for σ and b, we can find values for h and k. Planck actually did this, and he obtained values that agree well with those obtained later by other methods.

The simulation below shows the blackbody curve for a radiating object. It allows you to set the temperature anywhere from 200 K to 11,000 K. It shows intensity as a function of wavelength, and it shows the apparent color of the radiating body. Below the simulation is a note regarding the applications of this phenomenon to astronomy and other things.

Simulation by PhET Interactive Simulations, University of Colorado Boulder, licensed under CC-BY-4.0 (https://phet.colorado.edu).

The connection to astronomy (and other things):

Planck’s radiation law allows us to predict in detail the nature of the radiation of a body that has a particular temperature. Conversely, if it is possible to measure the intensity of the emitted radiation as a function of wavelength, we should be able to determine the temperature of a radiating body. This is what astronomers do to determine the temperatures of celestial objects, most commonly, stars. Most ordinary stars emit radiation similar to that of a blackbody, so measuring the spectrum of a typical star and thereby obtaining its blackbody curve, allows one to determine the star’s temperature, either by fitting the spectrum to Planck’s radiation law, or by finding the wavelength that corresponds to the maximum intensity and using Wien’s displacement law. (The structure of some stars is such that the material in their outer layers absorbs some of the outgoing radiation in a particular region, for example, the UV, thus creating a gap in their blackbody curves.)

Alternatively, if one can measure the radiancy of a star, one can use Stefan’s law to determine its temperature. For a star or other radiating object, a property that is intimately related to the radiancy is its luminosity, which is the total energy it emits per unit time, and which equals the radiancy multiplied by the surface area of the object (luminosity = 4πr2R). Astronomers measure a star’s luminosity by measuring its energy flux (energy transmitted per unit area per unit time, here at earth), and then multiplying by the area of a sphere whose radius is the distance between the Earth and the star. If it is possible to measure the diameter of the star, then one can calculate the surface area and divide it into the luminosity to get R, and then use Stefan’s law to find T.

Luminosity is proportional to the square of the radius of the object, and to the fourth power of its temperature; luminosity equals 4πr2R, which equals 4πr2σT4. In cases where it is not possible to measure the radius of the star directly, if one knows the luminosity and temperature of a star, one can determine its radius.

This direct use of Stefan’s law is probably not a common method for determining the temperature of celestial objects, but it does play an important role in the development of the method described below, which is commonly used.

As opposed to the spectrometric method described above, in which one obtains a plot of the intensity of a star’s radiation vs. wavelength, astronomers often use filters to measure the intensity of the light emitted over specific wavelength ranges. They typically use a standard set of filters, labeled U, B, V, R and I, for the wavelength ranges in which they transmit light. These letters stand for, respectively, “Ultraviolet,” “Blue,” “Visual,” “Red” and “Infrared.” Perhaps the most commonly used set is the Johnson/Bessel type. In this set, the U filter has a center wavelength (CWL) of 365 nm and a full width at half maximum (FWHM) of 60 nm, the B filter has a CWL of 440 nm and a FWHM of 100 nm, the V filter has a CWL of 520 nm and a FWHM of 90 nm, the R filter has a CWL of 630 nm and a FWHM of 120 nm, and the I filter has a CWL of 900 nm and a CWL of 300 nm. (See, for example, this page at Edmund Optics. You may see these listed as “Johnson-Cousins,” with an I filter whose transmission is closer to that shown for the Kron-Cousins I filter on the Edmund Optics page.) Other filters, of course, are also available, including those that transmit over narrower wavelength ranges than do those listed above. The measurement of the intensity of starlight in this way is called photometry. Astronomers use a variety of filter sets to make these measurements. The set described above is called UBVRI, and its use in making these measurements is called UBVRI photometry.

The shape of the blackbody curve of a star determines the relative intensities of the light emitted in the different wavelength ranges (U, B, V, R and I), and thus also the apparent color of the star. While it is not uncommon to refer to stars as having a certain color, and some types of star have color in their name, for example, white dwarfs and red giants, astronomers typically use a color index to characterize the colors of stars. To state what a color index is, we must first define magnitude.

The magnitude of a star is its apparent brightness, which is assigned a number on a scale that was first developed by Hipparchus sometime in the second century B.C.E. Hipparchus ranked the stars visible with the naked eye on a scale from 1 to 6, 1 being the brightest and 6 being the faintest. It happens that the difference from one number to the next corresponds to a factor of about 2.5 change in apparent brightness, and the difference between magnitudes 1 and 6 corresponds to a factor of about 100 in apparent brightness. This scale has been modified slightly and expanded. First, a change of 5 in magnitude, say from 1 to 6, is now defined to correspond to a change of exactly 100 in apparent brightness, and because these numbers refer to apparent brightness, they are called apparent magnitudes. The scale runs from the apparent magnitude of the sun at -26.8 down to that of the faintest star that either the Hubble or Keck telescope can see, at 30. If astronomers wish to compare directly the intrinsic brightness of two or more stars, they use a reference distance of 10 parsecs (3.09 × 1017 m, or 3.09 × 1014 km). Since magnitude goes as the inverse square of distance (see demonstration 76.06 – Inverse square frame), given the distance and apparent brightness of a particular star, one can calculate how bright it would appear if it were 10 parsecs away. Doing this allows direct comparison of the magnitudes of different stars, and the magnitude of a star calculated for a distance of 10 parsecs is called its absolute magnitude. (The unit name parsec is from parallax arc second, the distance from the sun for which an object viewed from both ends of a baseline 1 astronomical unit long (1 A.U., which equals 1.496 × 1011 m, or 1.496 × 108 km) exhibits a parallax of one arc second. The Earth’s orbit is 2 A.U. wide, so for determining the distance of an object in parsecs, the parallax is taken as half that observed between two measurements taken at opposite points in the orbit.)

A color index is the difference in apparent magnitude of a star as measured through two different filters. A variety of color indices exists, probably the most common being B-V and V-R. B-V is the most often used. This color index is the magnitude of the star measured through a B filter minus its magnitude measured through a V filter. There are well defined relationships between these color indices and the temperatures of the stars. For example, see Sekiguchi, Maki and Fukugita, Masataka. “A Study of the B-V Color-Temperature Relation”, The Astronomical Journal, Vol.120, no. 2 (2000), p. 1072. (Stefan’s law is used to establish the reference temperatures to determine the relationships between the color indices and temperature.) The table below gives three examples of stars with their B-V color indexes and temperatures. The data are based on those in Table 17.1 on page 389 in Chaison and McMillan, cited below.

Star B V Color Index

(B-V)Surface Temperature

(K)Color Rigel -1.44 -1.2 -0.24 20,000 Blue Sun -0.04 -0.69 0.65 6,000 Yellow Betelgeuse -0.5 -2.2 1.7 3,000 Red Because magnitude decreases with intensity, a star that emits more light in the blue region than in the visual region has a negative color index, and one that emits more in the visual than in the blue has a positive color index. The department of Astronomy Education at University of Nebraska-Lincoln has a simulation that shows the blackbody curve for a star at a given temperature (which you can adjust), the intensities of the light through U, B, V and R filters, and the color index, here. (Click on the tab labeled "filters." You can choose which color index to display (B-V, V-R, etc.)). Typically, to determine the temperature of a star, astronomers measure its magnitude with a pair of filters, each in turn. From the resulting color index, they then calculate the temperature.

In addition to astronomical applications, these blackbody radiation laws find great practical use in the design of a variety of devices used either for remote thermometry, infrared imaging or both, for example infrared cameras such as those made by FLIR, and various contacless thermometers used either in healthcare or in industrial settings, such as those shown here.

References:

1) Eisberg, Robert and Resnick, Robert. Quantum Physics of Atoms, Molecules, Solids, Nuclei, and Particles (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1974), ch. 1.

2) Halliday, David and Resnick, Robert. Physics, Part Two, Third Edition (New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 1978), pp. 1091-1096.

3) Chaisson, Eric and McMillan, Steve. Astronomy Today (Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1999), pp. 65-70, 380-381,385-389.

4) http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/thermo/stefan.html#c1 (Stefan-Boltzmann law).

5) http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/mod6.html (Blackbody radiation, Cavity modes, Planck radiation formula, Rayleigh-Jeans formula).

6) http://hyperphysics.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/wien.html (Star temperature, Wien’s displacement law).

7) http://spiff.rit.edu/classes/phys440/lectures/filters/filters.html (Astronomical spectra, filters, and magnitudes by Michael Richmond of R.I.T.).

8) http://spiff.rit.edu/classes/phys445/lectures/colors/colors.html (Photometric systems and colors by Michael Richmond of R.I.T.).

9) http://spiff.rit.edu/classes/phys440/lectures/color/color.html (Astronomical “color” by Michael Richmond of R.I.T.)).

10) Bessell, M.S. "UBVRI Photometry II: The Cousins VRI System, Its Temperature and Absolute Flux Calibration, and Relevance for Two-Dimensional Photometry" Pub. Astro. Soc. Pacific, Vol. 91, No. 543 (1979), p. 589.